In 1866, a circle of largely urban travel enthusiasts embarked on a mission to open up the Norwegian countryside for tourists and travelers alike. They founded the Norwegian Trekking Association, which had as a key premise to not only promote the experience of the authentic nature of Norway, but also to make this experience practically accessible. By paying close attention to the tensions between knowing, sharing, and experiencing wilderness in the activities of the Trekking Association, we can see how wilderness is a concept that has modern transport and information infrastructures at its core.

The Trekking Association built a network of footpaths and cabins in remote areas to make nature more convenient in the years following its foundation. This extensive infrastructure allowed travelers to experience nature in a controlled – even standardized – fashion, whether in rural areas, along fjords, in the highlands, in the forests, or in the rugged mountains. At the time, Norway had few urban centers, connected by the sea, by rough roads, and a nascent railroad network. The rest of the country was wild and untamed, or at least so it seemed from the urban perspective. The infrastructures developed by the Trekking Association brought this wild nature in reach of ever-larger groups of Norwegians.

The founders of the Norwegian Trekking Association wrote incessantly about the nature they experienced when traveling, the scenic sites they identified, the people they met, and the national identity they extrapolated from the landscapes they traversed. It was in nature and not in the urban they found the sources of a new and authentic Norwegian national identity after 400 years under Danish rule. They wrote the new national identity into being, while simultaneously writing a new nature into being. What’s just as important, they intended their knowledge of nature to be shared, as were the nature experiences they described.

We can see this in Reisehaandbog over Norge, an exceedingly popular book written by Yngvar Nielsen, published in 12 editions between 1879 and 1915. The 1915 edition had grown from the original 234 pages to be 540 pages long, containing several fold-out maps and illustrations. Later editions were split geographically into four parts. The books described travel routes across all of Norway in great detail, including travel distances, transport and lodging options, prices, itineraries, and scenic routes, as well as historical and cultural overviews and a general guide to trekking for inexperienced travelers. Over the years, Nielsen traveled repeatedly across all of Norway, both following and to some extent guiding the development of new transportation infrastructures.

Later he and others were joined by photographers like Anders Beer Wilse, who took photos of more or less everyone and everything, everywhere in Norway. Like Nielsen, Wilse traveled extensively and brought visual impressions of remote and scenic areas into the homes of Norwegians. This particular combination of nature and media is not only key to understanding the intertwined Norwegian ideas of wilderness and nation that developed, but also to understanding the privileged place that wild nature got in discourses of the value of different types of nature.

…it is a pity that it is so difficult to get to the most beautiful places and that you can’t have a roof over your head in the places that are furthest away from people.

Vinje pointed to the need for physical infrastructure development, to “improve certain mountain paths such as at Vøringfossen and Maristigen, and then build some cabins here and there in the mountain plateaus. And then people can look around without fearing for their lives and learn to know their country both scientifically and aesthetically.” In other words, the rediscovery and reinterpretation of the Norwegian landscape as a particular kind of wilderness was tied to the development of an infrastructure for convenient traveling– roads, bridges, food and lodging, as well as travel guides. Without this infrastructure, nature was simply too wild to provide authentic natural experiences for most travelers.

The Norwegian Trekking Association provided both, and was highly successful in its mission. In fact, the organization was so successful that its members soon began lamenting the new accessibility. A rapidly growing number of travelers discovered that while they enjoyed convenient access to nature, they did not enjoy all the other people there quite as much – a classic case of the tourist’s dilemma. In other words, the Trekking Association realized that through their work, nature had become culture. The wild was tamed through sharing. As a result, the 1933 general assembly of the Trekking Association declared that “we need to protect nature from ourselves.”

The organization thus reconsidered its own expansive activity to accommodate nature tourism in Norway and made a conscious effort to scale back, become less visible, and in particular less accommodating for cars. The wild was broken and had to be rebuilt.

The Trekking Association was not alone in driving the infrastructural development past the breaking point. In the last half of the nineteenth century, new railroads, roads, and boat routes were paired with a growing service industry of maps, guides, food vendors, and lodging, all aimed at urban national and international tourist-travelers. These infrastructures opened up formerly remote regions and connected them to the rest of the nation, but were profoundly intertwined with the work of writers, photographers, artists, and travelers, as well as private and governmental institutions that sought to articulate the cultural meaning of landscape on a national scale. The landscapes of the Scandinavian countryside became increasingly covered in a dense web of transportation infrastructures and cultural information layers. Wild nature and not quite so wild nature were closely intertwined here, and not so easy to distinguish.

Taking a cue from Steven J. Jackson, who argues in his essay “Rethinking Repair” that we should take breakdown, dissolution, and change as our starting point rather than innovation, development, and design, we could consider breakage and breakdown the starting point of our particular conceptions of wilderness, rather than an idea of wilderness emerging from a pure state of authentic and undisturbed nature. It is in dealing with breakdown we build a world – a nature, a wilderness – that we can live with and live in.

I have in these two posts asked what wilderness means in the information age, and what we see is that wilderness really starts with the information age. Information technology has a history that predates the computers in our offices and the cellphones in our pockets. While digital devices are obvious interfaces to information infrastructures, so were the media – maps, books, drawings, paintings, and photos – created and shared by 19th century travelers. The history of old and new media is thoroughly entangled with our idea of what wilderness is and should be.

If we consider how tightly entangled the first articulation of wilderness was with sharable media, we should adopt a more nuanced stance on this strange technological nature that wilderness can be said to be. Our definitions of wilderness have of course evolved over time, and the things the 1860s travelers called wild might not be the same as we call wild today. But we still find the same tendency towards defining wilderness and nature as an experience through sharing in media. Information technology and perpetual connectivity is not necessarily a threat to wilderness – yet full of contradictions and by no means unproblematic.

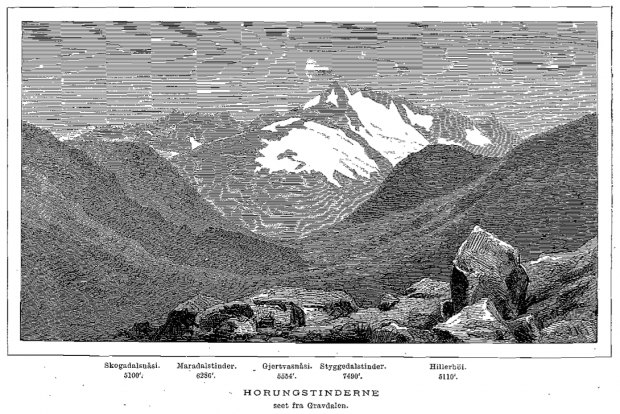

Featured image: “Horungstinderne,” Den Norske Turistforenings årbog for 1873.

This text was originally published on: http://www.antspiderbee.net/2015/09/09/knowing-sharing-and-experiencing-wilderness/ and will also be reproduced in the Ant Spider Bee book.