What does the experience of nature look like when filtered through digital devices? How wild is ”wilderness” in the information age? Such questions underpin many current attempts to articulate the authenticity of nature, made urgent by the increasing presence of smartphones, GPS trackers, social media, and other forms of connectivity in nature. Many such stories place nature and wilderness under considerable pressure from information technology, while others bring our attention to potential digital augmentation of nature. See for instance Yolonda Youngs’ digital wonderland and Sarah Wilson’s observations on “the natureness of nature” and the digital, and the Environment and Society Portal’s “Wilderness Babel” for some examples of the last category.

While it may not be all that fruitful to say that one side is correct and the other is wrong, it is obvious that nature is many things to many people. We can focus on a subset of nature in this post – the idea of wilderness, arguably the most ”authentic” form of nature. Even so, wilderness also makes it clear that nature is an intensely mediated space. While there are physical landscapes out there that we designate as “wilderness” we do so in the form of narratives shared in public in a variety of media, imbuing wild landscapes with meaning and significance.

William Cronon’s influential and (for some) controversial 1991 article ”The Trouble with Wilderness” has shaped environmental historians’ understanding of wilderness in fundamental ways. Cronon leans quite heavily on the history of ideas and the history of religion when looking for the historical articulation of a particular idea of the sublime in nature – in other words, the thing we now know as wilderness. And in this process of articulation, wilderness was not only tamed, but also made as a cultural category. While the landscapes we designate as wilderness existed as physical entities before we came up with the modern idea of wilderness, it held an entirely different meaning. This double move is a classic constructivist approach that made Cronon unpopular among nature conservationists and activists. Scholars like Eileen Crist argues that considering nature as socially constructed is an ideological move that is “as dangerous to the goals of conservation, preservation, and restoration of natural systems as bulldozers and chainsaws.”

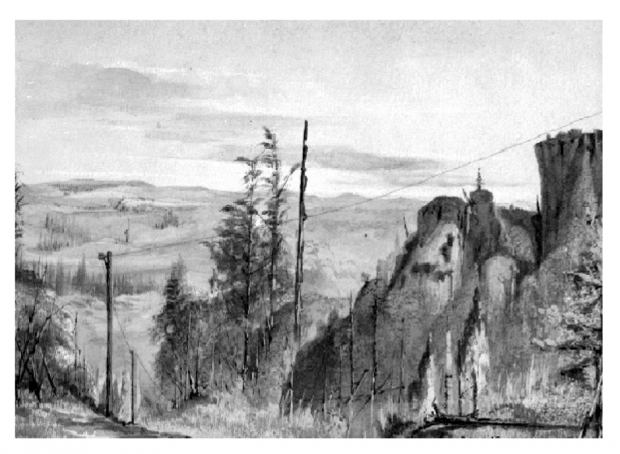

“Wilderness” as a cultural concept has evolved through this intertwining of landscape and narrative over long time periods, but can also go through rapid changes in short time. At the moment wilderness became a thing, something we as a society would recognize as wilderness – it became so to a large degree through media. What’s more, it was enabled and preserved by particular kinds of infrastructure. As a cultural concept, it is not entirely in our own heads, but shared (if often contested) between us and made material in a variety of ways. If we think about wilderness in these terms, as embedded in media and information infrastructures, seeing wilderness as fundamentally in opposition to digital becomes difficult.

With infrastructure, I here mean particular types of technology; not individual artifacts, but large systems, interconnected and distributed . In the classic study Sorting Things Out by Geoffrey Bowker and Susan Leigh Star (1999), they pushed against the idea of infrastructures as technology, and instead directed our attention to the way ideas and categories come into being, and how infrastructures make them become ordinary.

Furthermore, infrastructures have spatiality in ways that aren’t as obvious in artifacts. As Paul Edwards writes, “mature technological systems – cars, roads, municipal weather services, sewers, telephones, railroads, weather forecasting, buildings, […]– reside in a naturalized background, as ordinary and unremarkable to us as trees, daylight, and dirt. Our civilizations fundamentally depend on them, yet we notice them mainly when they fail….” (185) Can we say the same thing about wilderness; we tend to notice technology as a threat to nature when the infrastructures that bind nature and technology together break?

Breakages demonstrate how infrastructures are intimately tied up with knowledge. They are both ways of doing and ways of thinking. Yet, infrastructure becomes invisible: when it works, it retreats into the background, and only becomes visible when it breaks. This does of course make breaking points valuable for scholars like us. What can we find the breaking points of the infrastructure of wilderness? I think one place is simply when it becomes visible – as a danger to nature. In order to function as infrastructure that can support and enable the wilderness story, a careful balancing act needs to take place, one that is both practical and rhetorical.

In the next post in this series, I will use a concrete historical case to trace how the increasingly dense web of transportation infrastructures and cultural information layers in the late 19h century Norwegian countryside not only connected the urban and the wild, but also served to define and articulate these as separate categories. I will pay particularly close attention to the tensions between knowing, sharing, and experiencing wilderness that followed new media and new mobility in this period, and how these tensions came into play when wilderness protection became an issue in the beginning of the 20th century. Today, when the wilderness experience seems to be more endangered (or illusory) than ever, it is critical that we pay close attention to how cultural and technological mediation creates connections between landscapes, values, actors, and nations.

Image: Collins overland telegraph line, John Clayton White (1835-1907), public domain, BC Archives #PDP02915 via Wikimedia.

Originally published on http://www.antspiderbee.net/2015/08/13/breaking-the-wild-with-digital-devices/ and also included in the Ant Spider Bee book.